In a parallel universe, there is a tower in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It was commissioned by the sultan of the slice, Domino’s Pizza founder Tom Monaghan. It bends out at an angle above a lake—and thus, it earned a 10/10 nickname before it was even built: The Leaning Tower of Pizza.

In this parallel universe, R. Buckminster Fuller redefined Toronto’s skyline with a 400-foot-tall crystal pyramid. Frank Lloyd Wright created a (literally) mile-high skyscraper in Chicago that towers above the Burj Khalifa, currently the world’s tallest building—which actually resembles a miniature of Wright’s plans.

Who wouldn’t want to live in this strange architectural wonderland?

Regrettably, none of these plans ever went forward. But they make for wholly fascinating reading in Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin’s new book, Atlas of Never Built Architecture. Across nearly 300 projects from 80 countries, the book thrives on the element of discovery—and ultimately the authors say you can glean more about the art of architecture from the unbuilt than the built.

“You learn more from defeats than from victories,” Lubell says.

What could have been

The authors liken existing architecture to the tip of the veritable iceberg. The unbuilt is everything that underpins it—projects waylaid by war, regime changes, economic depressions, and myriad reasons beyond. In addition to all the lessons that failed projects carry in their postmortem (and how deeply they, no doubt, inform an architect’s future projects), what is most fascinating here is seeing the raw materials of an architect’s complete vision in rarely, if ever, published sketches, paintings, and more.

“It’s what an architect truly had in mind,” Goldin says. “By the time something gets built, so many people have stepped on it that its purity has certainly been lost.”

Lubell and Goldin worked on the massive compendium for around four years—but the project technically dates back to 2010 or so, when they began cocurating exhibitions on never-built architecture in Los Angeles (2013) and New York (2017). As hobby genealogists or anyone else who has ever plumbed the past for official records know, it can be tough sleuthing work. But for the authors, that’s the whole point.

“We’re both obsessed with the treasure-hunt part of it,” Lubell says.

Though the two employ various tactics to uncover projects, one key strategy is to study the famous (and less-than-famous) architects who worked in a given city, and then dig for their unbilled works in archives at universities and museums, reverse-engineering the process of building a building. It all makes for a brilliant alternate timeline. And, well, perhaps a study in possibility.

“A theme that runs through the book,” Goldin says, “is that [these] architects had a sense of derring-do. And I think that’s really, really something critically missing today.”

From among the many projects in the book, here are five of the authors’ favorite unbuilt buildings.

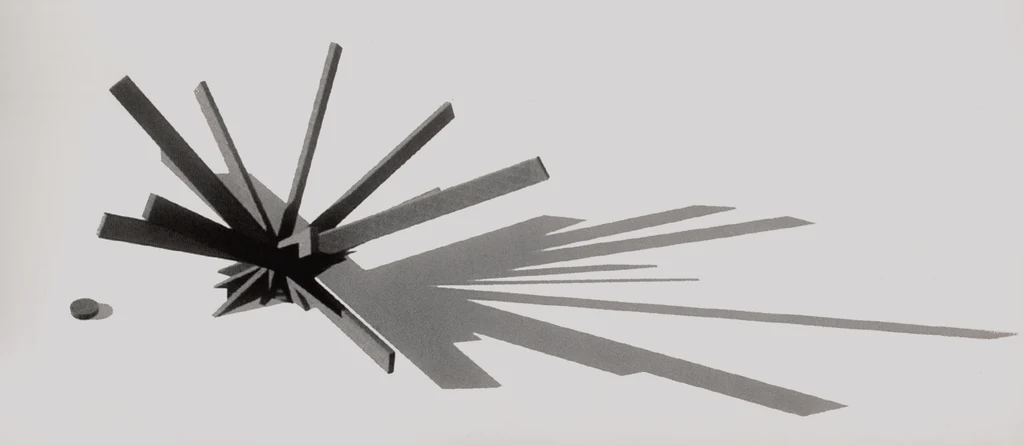

The Bay of Pigs Monument (1962)

Following the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, Cuba launched an international design competition for a monument and museum on the inlet showcasing weaponry and other items. Brazilian architect Fábio Penteado didn’t win, but Castro personally liked his design best, so he awarded Penteado the contract anyway. Penteado intended to bury the museum under the beach and let the spiky, striking geometry of his monument serve as a singular metaphor for revolution, as the book frames it.

“It’s a really, really daring work,” Goldin says. “These towers or shards of concrete emerging out of the sand like rifle barrels. . . . It’s expressive in the way that it takes concrete in its most sculptural character, and just blasts off.”

Ironically, a coup in Brazil kept Penteado from leaving his country to bring it to life.

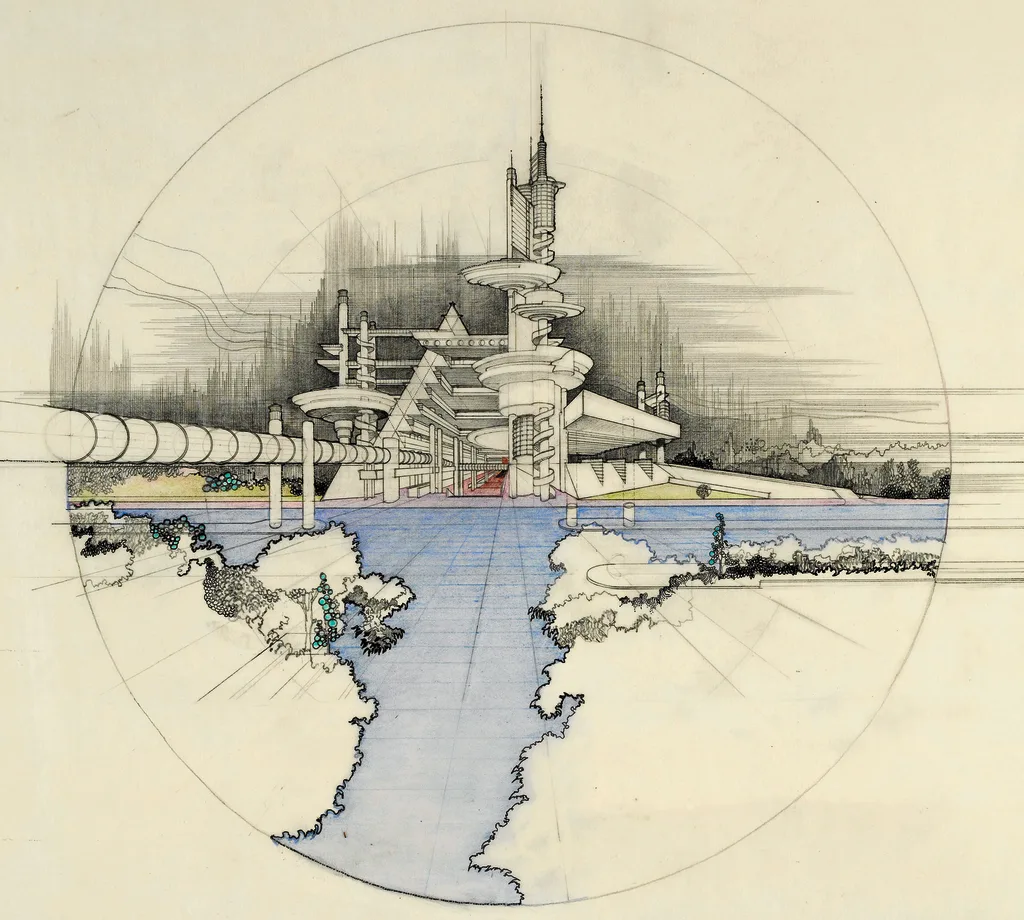

Fiat Novoli (1987)

According to Atlas of Never Built Architecture, Aldo Loris Rossi’s motto was “break the boxes” . . . which is clearly what he was attempting to do in this business/residential center at a former Fiat factory just outside Florence, Italy. With the vibe of a ’70s/’80s fantasy matte background painting, it would have put a wholly surprising twist on a Renaissance city whose architecture is uniquely frozen in time.

“You start looking at his drawings, and you realize, Oh my God, this guy is an overwhelming genius of just throwing stuff at you in ways that are completely unexpected,” Goldin says. “What is this Fiat [project drawing] other than an incredible expression of speed, movement, production, and industrial intensity . . . ”

Despite all of it, the mundane killed the fantastical: the municipal administration turned over.

Arriyadh Science Complex (1988)

Douglas Cardinal is known for the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (2004), but long before that he won a competition to design a science center in Saudi Arabia. He married cues from the desert and ancient dwellings with the cosmic (and a monorail!). Saudi astronaut Sultan bin Salman Al Saud—the first Muslim to fly in space—was a key proponent of the initiative, but according to Lubell, found himself at odds with the royal family over the country’s future.

“So that project, like a lot of projects that have happened in autocratic regimes, went away, and you never really hear about them again.”

Monaghan Farm Tower (1987)

As it happens, Domino’s Pizza founder Tom Monaghan was a preeminent collector of Frank Lloyd Wright items. So he commissioned architect Gunnar Birkerts to design a Domino’s campus inspired by the architect of his fascination. At its center: the 30-story “Leaning Tower of Pizza,” which lurched forward by 15 degrees because Birkerts, bored with designing vertical structures, felt they were too “neutral.”

In the end, Monaghan sold Domino’s, and the Leaning Tower of Pizza would remain, um, half-baked (sorry).

Yala Beach Hotel (1968)

Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa invented an architectural style by “ripping open the bungalows built by British colonizers in his native Colombo” and overhauling them, melding Modernist ideas with the natural beauty of the island. Plans for his Yala Beach Hotel included three sets of cottages—one of cruciform tree houses, one of thatch-roofed rock houses, and one of sand houses seemingly carved into dunes. It was design born of the landscape, ultimately in celebration of it.

“It just felt like this distilled his particular gift for an understated language,” Goldin says. “It’s very subtle. It has an inflection of place that very few architects are willing to subsume their egos to—and I think that was his gift.”

What became of the plan?

“I wish I knew,” Goldin says. “This is one of the problems when you’re dealing with the topic that Sam and I are dealing with. Often, you end up getting really close to the end of the story—and then you don’t get the end of the story.”